|

|

关于公平:设计的有力与无力

On Equality: The Power and Powerlessness of Design

张利/ZHANG Li

现任联合国人权事务高级专员扎伊德·拉阿德·侯赛因即将于本月末卸任。虽然他还未卸任,但对他任内的遗产巨匠似乎已经有了共识:一方面,他直言不讳的苛刻言论使其与世界主要国家交恶;另一方面,他在真实世界中所创作发明的实际业绩微乎其微,使他最终不过是又一个行将被人遗忘的政客而已。

侯赛因式的例子其实不鲜见。在涉及为社会公平而进行的奋斗时,掷地有声的豪言壮语与软弱无能的现实干预所形成的强烈反差,持久以来一直是诸多精英与知识分子难以逃脱的宿命模式。建筑师对这种模式固然其实不陌生,至少在过去的几十年里是这样。

伯纳德·鲁道夫斯基的《没有建筑师的建筑》、亨利·列斐伏尔的《城市权》和哈桑·法赛为穷人所做的住宅是战后20年内较早关注社会公平问题的建筑案例,前两个通过写作,后一个通过实践。与之相伴的文化和媒体事件,尤其是在MoMA的展览《没有建筑师的建筑》,帮忙把他们的学术关注树立成一种另类的、以乡土建筑为重心的语境,与1960年代末的国际建筑话语形成了鲜明的对比。这一语境的学术兴趣基本上存在于两个方面:从美学上讲,是世界各地非建筑师建筑所承载的工艺与智慧;从伦理上讲,则是维系发生这些建筑传统的社群的尊严,以及建造活动如何贡献于具体地区的社会融合。

没过多久,这一语境中更偏社会学的部分就获得了更深入的发掘。坂茂的建筑开启了一种将富勒式的快装结构方案与紧急情况下的人道主义救援结合起来的思路。正是因为他的开创性工作,世界各地的灾区已经呈现了一种新的志愿者群体——建筑师,为灾民做轻盈、好看、能够快速装配的建筑。在大中华区,我们从本世纪初就看到了类似的做法,包含谢英俊在1992年地动后的作品以及朱竞翔近期的项目。

同样是针对社会问题,像迪埃贝多·弗朗西斯·凯雷和卡梅隆·辛克莱这样的人走了一条截然分歧的道路。他们进一步远离传统建筑话语的舒适圈,浸入到社区生活的日常之中。他们创作发明了基于可利用资源与技术的建筑,有时其饱含诗意的作品甚至完全来自于一时权宜之计的灵感。在这个方向上,大中华区也有很多好的案例,首先是李晓东的乡村三部曲,然后是林君翰的城乡架构系列,然后是无数的新锐建筑师走向广大的中国农村。

当下,越来越多的建筑将伦理置于美学之上。在这种浪潮的鼓舞下,越来越多的建筑师把为穷人做设计当作是一种不成回避的义务。然而,如果我们真心希望通过设计来给现实生活带来积极改变的话,我们就必须提出并解答一些基本的问题。如果我们仔细回顾一下自法赛以来这一流派中诸多备受推崇的案例,特别是如果我们近距离观察一下这些案例在建成后的长时间使用,我们会发现一个令人不安的事实。大多数项目,无论是住宅、教育、医疗还是文化建筑,往往更善于提高外部人士(大多是生活在城市环境的中产阶级)的意识,而不是改善内部人士(本地居民)的生活水平。这些项目所发生的最好的效果是在大灾之后迅速地兴建起足够数量的呵护所;最坏的情形则发生在那些最懦弱的社区,让本地的妇女和儿童在其实欠好用的建筑里充当照片的舞台布景,用以证明建筑师的光辉。

本期《世界建筑》的主要目的是扫描为穷人做设计的现状,提供一个切片式的记录。连同这份记录,我们还想提出三个问题,每个问题指向一个特殊的关注层面。对于这些问题,我们也许能从本期发表的项目中找到谜底,也许不克不及。

第一个问题指向的是为公平而设计的流派全体:在设计的“能”与“不克不及”之间,界限究竟在哪里?我们已经不大可能像希格弗莱德·吉迪恩和克里斯托弗·亚历山大那么乐观(或自负,这取决于你如何看待它)——这两位碰巧都相信建筑可以而且应该改造人的行为,或设计实际上能够教给人们该如何生活。显然,我们都感受了技术至上的现代主义城市所带来的巨大痛苦——他们简单地把我们当作了机器零件——现在我们是否又要把这种设计理性带给处所社区呢?

第二个问题指向这些项目的运行方案:除建筑师和本地人之外,我们是否需要一个强大的第三方群体来确保我们设计的建筑能持久发挥作用?如果是的话,该第三方是否应该介入设计过程?到目前为止,大多数涉及公平的项目设计都强调其自发的社会功能。学校、紧急住所、图书馆、诊所、本地工坊是最常见的类型。为了延续运行,他们需要教师、房屋管理员、图书馆员、医生、企业家以及大量的资源。为了提供这些资源,至少在中国,你需要获得本地政府的支持,而且有一个真正介入运营的投资者。

第三个问题,也是最难的一个,指向设计自己:建筑是面向城市中产阶级这些局外人的,还是提供给(通常是)乡村内部人士的?不生活在一个特定的气候中,要想把建筑设计得适应这个气候是很困难的。不生活在一个特定的人群中,要想建筑设计得融入这个人群则是根本不成能的。鉴于这些社区通常是那么偏远,设计往往要以快速访谈和现场查询拜访为依据,而这些有限的依据又往往引向太多的假设和推测。也许世界各大城市都越来越相像,因而在城市中进行假设和推测还是可行的;而每个萧条的偏远社区却是唯一无二的,我们无法在一个社区中引用另一个作为参照。为了查询拜访和解释这种怪异性,入门级的人类学实践是必不成少的。

为了给穷人做设计而给穷人做设计是不敷的。现在已经到了建筑师在低收人群体前放下身段的时候了。□

Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, the current UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, is stepping down this month. His legacy seems to have already been fixed: an outspoken rhetoric in words putting him in crossfires with all major states around the globe, and a disappointing score sheet in real-world achievements making him yet another politician to forget.

Al Hussein's case is not unfamiliar. When it comes to the struggle for equality, power in words and powerlessness in real-world interventions have long been the fateful pattern for many elites and intellectuals. This pattern is certainly no stranger to architects, at least for the past few decades.

Bernard Rudofsky's Architecture without Architects, Henri Lefebvre's "Right to the City" and Hassan Fathy's dwellings for the poor were among the post-war-years examples in architecture, writing or practice, to address the issue of equality. Accompanied by culture and media events, not least the Architecture without Architects exhibition in MoMA, they effectively setup vernacular architecture as an alternative discourse in the dense of the late 1960s. The academic interest was basically a two-fold one: aesthetically it was about the craft and wisdom of making of non-pedigreed architecture from all over the world; ethically it was about the dignity of the communities that sustained these building traditions and how the practice of building may contribute to local social coherence.

It didn't take long before the social part of the discourse got explored in greater depth. The architecture of Shigeru Ban initiated an approach that marries Fullerian structure solutions with emergency humanitarian situations. Thanks to his pioneering work, disaster-hit communities in different parts of the world have been able to see a new species of volunteers - architects doing light and good-looking, rapid-assembled buildings for them. In the greater China region we have seen similar approaches starting from the turn of the century, including Hsieh Ying-Chun's works after the 1992 earthquake, and various recent projects by ZHU Jingxiang.

Also aimed at social issues, people like Diébédo Francis Kéré and Cameron Sinclair took a very different path. They step further away from the comfort zone of traditional architecture discourse and dive into the troubled water of daily community life. They produce architecture that is based on available resource and technology, sometimes even making poetic works entirely out of ad-hoc solutions. There are also plenty of good examples in the greater China region in this direction, first demonstrated by LI Xiaodong's rural trilogy, then by John Lin's rural framework series, then by countless emerging architects going out to work in the vast Chinese countryside.

Encouraged by the growing evidence of architecture putting ethics before aesthetics, more architects are now finding it an obligation to design for the poor. Yet serious questions need to be asked if we are serious to ensure positive real world social changes through our designs. If we look back closely on the highly revered projects in this genre since Fathy, particularly if we scrutinise the life of these projects since their completion, we'll have an unsettling observation. Most projects, be they residential, educational, medical, or cultural, are more capable of raising the awareness of the outsiders (mostly middle class living in an urban environment) than raising the living standards of the insiders (local inhabitants). Best case scenarios are usually found in the aftermaths of disasters where shelters are made abundantly and quickly. Worst case scenarios are invariantly found in the most vulnerable communities, where local women and children are used in staged photos to prove the glory of architects.

It is therefore the key interest of this WA number to provide a snapshot of the status quo of designing for the poor. Along with this snapshot, we would also like to ask three questions which may or may not be answered by the projects published. Each of these questions addresses a particular scope of concern.

The first question relates to the design for equality genre as a whole: where is the boundary between what design can and what design can't? We all remember the different forms of optimism (or complacency depending on how you look at it) from Siegfried Giedion and Christopher Alexander who both happened to believe that architecture could and should practice active behaviour modification, or that we could actually design people's lives. Yet we all suffered greatly from the cities created by technocratic Modernism that simply treat us like machine parts. Are we to bring this design rationality again to the local communities?

The second question relates to the programmes of such projects: do we need a powerful third party, other than architects and locals, to run long-term programmes in the buildings we design? If so, should such third party be included in the design process? Up to now, most design for equality projects are built upon social programmes. Schools, emergency lodgings, libraries, clinics, local craft workshops are the most common types. To last long, they would need teachers, house keepers, librarians, doctors and entrepreneurs, along with huge amount of resources. To provide such resources, in China at least, you'll need the support from the local government, and a truly engaged investor.

The third question, and the most difficult one, relates to design: is the building speaking more to the urban middle-class outsiders, or the (usually) rural insiders? Fitting a building into a specific climate is hard without living in that climate. Fitting a building into a specific community is impossible without living in that community. Quick interviews and site surveys, which is usually the case given how remote these communities are, only lead to assumptions and speculations. While all major world cities are getting more and more alike, each depressed community is still unique. To investigate and to interpret such uniqueness, an architect needs to practice some basic anthropology.

Designing for the poor for the sake of designing for the poor is not enough. Time for architects to get humble before the poor. □

作者单位:清华大学建筑学院/《世界建筑》

全文刊载于《世界建筑》201808期P8-9。转载请注明出处。

简讯

06

篇首

08 张利

关于公平:设计的有力与无力

为低收入群体的建筑

10 王雅捷

基于社区查询拜访的北京市公平与包涵现状及规划对策分析

15 李耕

低收入群体的社会学视角及其对空间设计的启示

18 戴安娜·E·戴维斯

通过社会住房战略投资建设更美好城市

26 吕品晶

见人见物见生活的乡村改造实践

32 林君翰,约书亚·伯尔乔夫/城村架构/香港大学

金台村重建项目,巴中,中国

38 迈克尔·毛赞建筑事务所

星公寓,洛杉矶,美国

44 张悦,郝石盟,朵宁,李培铭,王钰

福绥境胡同50号“开间更新”院,北京,中国

52 谢英俊建筑师事务所,常民钢构

未来之村,卡通泽,尼泊尔

58 丹尼尔·费尔德曼,伊凡·达里奥·基尼奥内斯

瓜达尔儿童中心,考卡,哥伦比亚

64 1+1>2 建筑事务所

森林之花,太原,越南

70 克恩顿州应用科学大学,集体营造NPO

姆扎巴桥,东开普,南非

76 阿尔弗雷多·布利耶博格,休伯特·克隆普纳/城市智库

公交缆车——正规城市与非正规城市的桥梁,加拉加斯,委内瑞拉

80 DnA建筑设计事务所

红糖工坊,松阳,中国

88 1+1>2 建筑事务所

索热社区之家,和平,越南

94 马科斯·科罗内尔·布拉沃/PICO集体

文化制作地带:城市创意单位,瓜卡拉,委内瑞拉

98 直向建筑

所城里社区图书馆,烟台,中国

特别报导

104 二台镇华夏之星初心图书馆,张家口,中国

106 项琳斐

华夏之星初心图书馆设计师朵宁访谈

110 叶扬

华夏之星初心图书馆承建方昆仑绿建访谈

112 钱晨

重建乡土的纪念性——三座初心图书馆

116 汪硕

开启自由空间——第16届威尼斯建筑双年展侧记

120 李翔宁,姚伟伟

何不再问“自由空间”——第16届威尼斯国际建筑双年展中国国家馆策展记录与思考

124 郎宇兵,李兴昌

2018维纳博艮砖筑奖:高质量砖建筑的颂歌

改进建筑60秒

126 戴俭,宋昆

念书

127 潘曦,周渐佳

本期作者

128

工程实录

130 余静赣,林睦嘉

自然造校,低而不贱——谈江西美术专修学院低本钱建造哲学

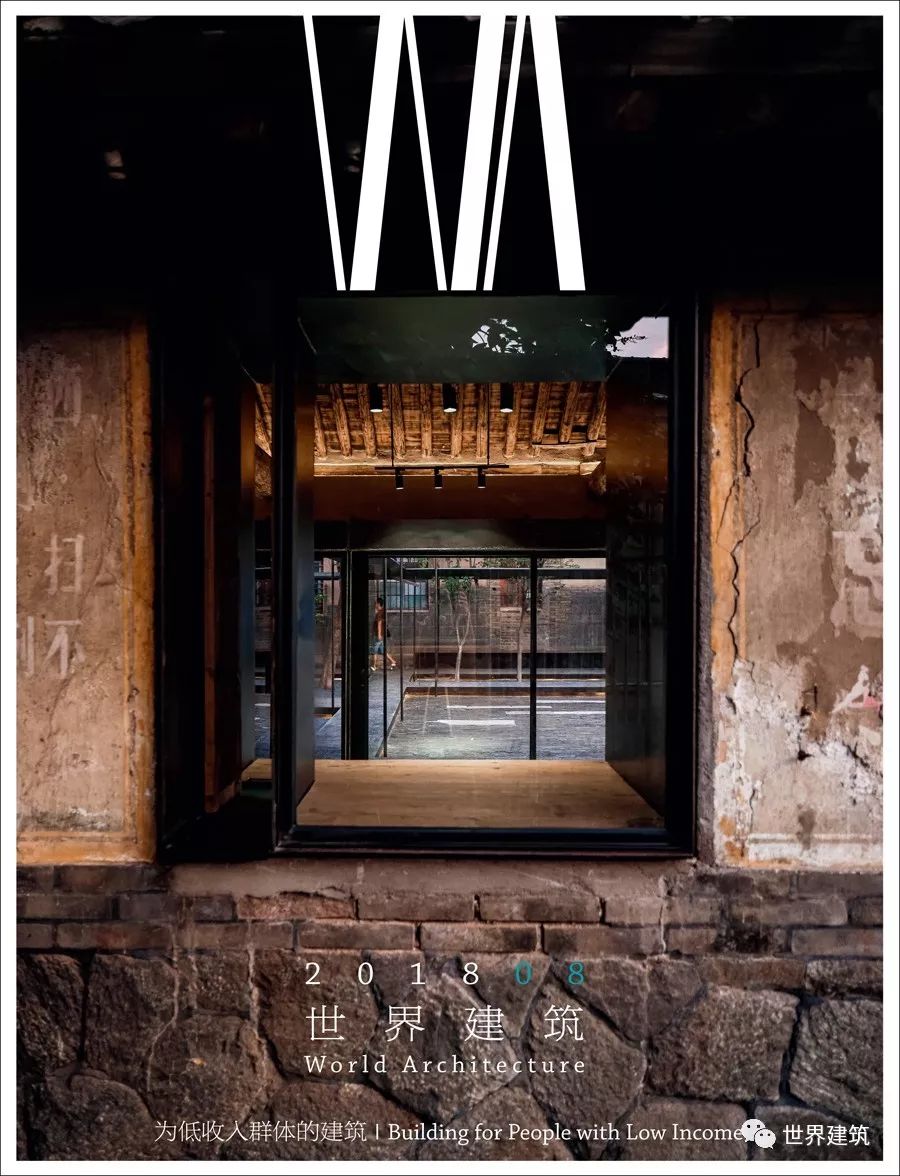

封面摄影:苏圣亮

本期责编:叶扬

点击页面下方“阅读原文”购买2018/08期《世界建筑》杂志

本期微信编辑:路培

|

温馨提示:

1、在论坛里发表的文章,仅代表发帖人即作者本人的观点,与本网站立场无关。

2、论坛的所有内容都不保证其准确性、有效性、时间性;其原创性以及文中陈述文字和内容,未经本站核实。请读者仅作参考,并请自行核实相关内容。阅读本站内容因误导等因素而造成的损失,本站不承担任何责任。

3、当政府机关依照法定程序要求披露信息时,论坛均得免责。

4、若因线路及非本站所能控制范围的故障导致暂停服务期间造成的一切不便与损失,论坛不负任何责任。

5、如果本站文章内容有侵犯您的权益,请发送信息至996741585@qq.com,我们会及时删除。

|

|Archiver|手机版|小黑屋|围炉码头|工程合作主题商务空间|成都汇赢建设咨询有限公司

( 蜀ICP备19016737号 )

|Archiver|手机版|小黑屋|围炉码头|工程合作主题商务空间|成都汇赢建设咨询有限公司

( 蜀ICP备19016737号 )